By Luigino Caliaro.

On October 23rd eighty years ago, Francesco Agello and the Macchi Castoldi M.C. 72 achieved the absolute world speed record for a piston-powered seaplane; a record which still stands to this day.

“To beat the Brits: that is one of the reasons why the Macchi-Castoldi M-C 72 was built. To win the Schneider Trophy, the historical hydroplane competition was first announced in 1911, in which Italy had had its fair share of triumphs until 1927 when the United Kingdom had started an uninterrupted winning streak. Fascist Italy felt it had to change that.”

The years following the First World War have long been considered the “Golden Age of Aviation” due to the rapid technological progress building upon the foundations laid in wartime. In Italy, this period coincided with exceptional growth in aviation, particularly in the second half of the 1920s. This was thanks partly to the leadership of Italo Balbo, nominated as Secretary of State for Aviation on November 26th, 1926. He managed to promote and demonstrate the high level of Italian aeronautical achievements through a series of aviation exploits of global impact. Amongst these efforts stand out the Roma-to-Tokyo flight, and a world record flight on a closed circuit (Montecelio-to-Tours), both by Arturo Ferrarin in 1921 and 1928 respectively; the two long-distance flights by Francesco De Pinedo, who in 1925 left Sesto Calende to arrive in Tokyo in an SIAI S.16, and in 1927 departed from Cagliari Elmas for the two Americas, later returning to Rome; and the Arctic exploits of Umberto Nobile, who in 1926 and again in 1928 reached and explored the North Pole in the airships “Italia” and “Norge”.

The cruises in the Western and Eastern Mediterranean (1928 and 1929), the transatlantic mass crossing (1930), and the Crociera del Decennale (1933) also held the world’s attention. Nevertheless, the effort with the greatest resonance in Italian public opinion was the Regia Aeronautica’s participation in the Schneider Cup races. The desire to win this trophy drove the Aeronautica Militare to spare no expense.

In 1928 they created the Scuola Alta Velocità (High Speed School) at the seaplane base in Desenzano del Garda under the command of Colonnello Bernasconi. The Ministero dell’Aeronautica considered the creation of such a specialized unit absolutely necessary following the dismal Italian performance at the Schneider races in Venice during 1927. The scarlet-colored Italian seaplanes, the supposed favorites, lost to the British Supermarine racers which proved more advanced and mechanically, far more reliable. In the Scuola Alta Velocità, the Regia Aeronautica had created an extremely specialized team, which would work in close cooperation with the Italian aviation industry, and produce highly skilled pilots and engineers dedicated to the singular goal of permanently winning the trophy; achieved only by the team which won at least three competitions over a five year period.

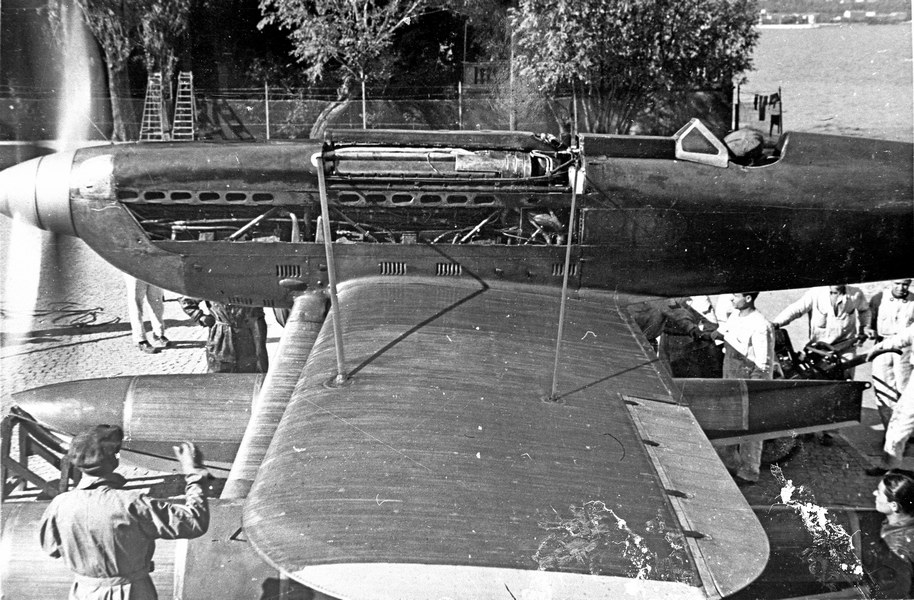

Unfortunately, at Calshot in 1929, the Italian aircraft again failed to win the competition due to technical problems and the imperfection of their engines; giving Britain the opportunity to win the trophy outright in the subsequent competition in 1931. Macchi had already built the majority of the nation’s attractive but underperforming seaplane racers, but the Aeronautica felt they were up to the job, and ordered the company to develop a new seaplane racer powered by the new FIAT AS 6 engine. From the pen of designer, Castoldi flowed a drawing of a beautiful and lithe floatplane, with clean aerodynamic lines, low drag, and reduced weight. They designed the wing using duralumin with asymmetrical biconvex profile, and tail stabilizers of wooden construction. The revolutionary FIAT AS-6 24 cylinder V-engine could produce more than 2,500 hp and drove two large, coaxial, contra-rotating propellers. The hugely powerful engine produced prodigious amounts of heat which demanded maximum available cooling area, so Macchi designed the radiators to lie flush with the wing and float surfaces.

The M.C. 72 was an amalgamation of all the latest technology, and as such rode the ragged edge of what was possible. As powerful as it was, it was a delicate balance to get it all to work reliably. Unfortunately, the new engine suffered from serious problems caused by dangerous backfires, which led to two fatal accidents involving pilots Monti and Bellini. These tragedies resulted in an Italian request to postpone the competition, but the British refused to budge, so the Regia Aeronautica felt compelled to pull out of the 1931 races. With the American team having dropped out previously, only the British ended up flying the race with their Supermarine S.6As and S.6Bs. The British wanted the race to be credible, and had designs on airspeed records as well, so the pilots pushed their aircraft to the edge, with the result that S.6A N247 crashed taking the life of its pilot G.L. Brinton. Predictably, of course, they did succeed in completing the race and won the Schneider Trophy outright with Flt.Lt. John Boothman successfully flew to victory in S.6B S1595 (now on display in London’s Science Museum).

At this point, the Scuola Alta Velocità seemed to have outlived its usefulness, as the principal goal for its founding, winning the Schneider Trophy, was now irretrievably lost. Nevertheless Italo Balbo, conscious of the advanced level of technology and human performance reached, decided to entrust the unit, recently renamed the Reparto Alta Velocita or RAV (High-Speed Unit), with the task of breaking the airspeed record. A British pilot, Flt.Lt. George Stainforth had set the speed-to-beat of 655 km/h (407.5mph) in Supermarine S.6B S1596 just over two weeks after the 1931 Schneider races.

In reality, the RAV received three primary objectives: i) break the speed record, ii) set the absolute record for speed over a 100 km distance (and therefore win the Coppa Bleriot created by the French pioneer for the first pilot to fly for 30 minutes at an average speed greater than 600 km/h), and iii) to participate in all the other international competitions of the period in which the speed element played an essential factor.

All RAV personnel set to work on the M.C. 72, believing the aircraft, once perfected, could easily achieve all these targets. Finally, by early 1933, the design team had mostly resolved the major engine problems, partly through the novel use of new, higher octane fuel mixtures, but principally by re-dimensioning the engine and adopting new carburetor tubes. With the serious flaws overcome, a newer spark plug design enabled the RAV engineers to boost the AS-6 engine’s power to over 3000 hp. The RAV chose Warrant Officer Maresciallo Francesco Agello, the last surviving pilot of the four originally tasked for the Schneider Trophy races, to fly the M.C.72 on its record attempts. He was the perfect man for the job, with exceptional experience and capability in regular flying duties and as a test pilot. Agello started with a series of “preparation flights”, and by early April 1933 both plane and pilot were ready to challenge the records. April 10th, 1933 was the triumphant day. For almost a week the team had waited for the ideal weather conditions, and in the morning Colonel Bernasconi took to the air over Lake Garda to conduct a check on the weather and visibility. Upon his return, Bernasconi gave the go-ahead for the flight. The ground crew pushed the M.C. 72 down the slipway to the lake, with Agello at the controls. Agello commenced the take-off run quickly and flew the five required laps over a 3 km course, identified on the surface of Lake Garda by red and white buoys. Along the course, intermediate stations housed the official FAI timekeepers. These men from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale were independent witnesses from the regulatory body to ensure Agello had flown the laps in accordance with FAI regulations. They also recorded the lap times. At the conclusion of the five laps, the commissioners were required to calculate the average lap time, with the possibility of excluding the slowest lap. After passing correctly in front of the time-keepers’ positions, Agello landed back at the seaplane base having been aloft for just 20 minutes and 32 seconds. The base personnel at Desenzano greeted him with rapturous applause, as they were certain he’d smashed the records.

The FAI officials agreed, recording that he’d beaten the previous absolute world speed record by some 27 km/h, with an audited average lap speed of 682.403 km/h (425mph). Despite the euphoria of the moment, in the following days, Col. Bernasconi and all the RAV personnel were convinced that this limit could be extended further to perhaps 700 km/h or even 750 km/h. The RAV had achieved its first target of attaining the world speed record, but there were still other records to overcome.

It is of note that during the summer of 1932, Col. Cassinelli had won the Coppa Dal Molin at the Zurich international competition of speed, flying at an average of 346 km/h (214mph) in a FIAT CR 30 aircraft, while Ten Scapinelli achieved second place. For the assault on the other records, however, as the banks of Lake Garda did not lend themselves to the establishment of a route of more than 100 km, and even less to permit a track required for the Coppa Bleriot, Col. Bernasconi decided to undertake the two trials along the almost straight Adriatic coastline, identifying an ideal stretch between the city of Ancona and just north of Pesaro for the 100 km circuit, and as far as Porto Corsini for the Coppa Bleriot leg. In the meantime, on September 26th, 1933, the RAV gained another prestigious victory, when Capt. Baldi and Ten Buffa conquered the Coppa Bibesco flying in a two-seat FIAT CR 30 from Rome to Bucharest, covering the 1,140 km (707 miles) in 3 hours 12 minutes at an average speed of 356 km/h (220mph). A few days later, on October 8th, Col. Cassinelli broke the world absolute speed record over a 100 km course at an average of 629.730 km/h (389mph), while on October 21st, Ten Scapinelli won the Coppa Bleriot for Italy, covering the required 30 minutes flight at an average speed of 619.374 km/h (383mph). So 1933 closed as a year full of success for Italy and for the RAV. However, RAV still dreamed of achieving the 700 km/h speed target. Everyone believed that 1934 would be a successful year, but they had to wait until autumn to finally break the 700 km/h barrier.

In the preceding months, the engineers had worked furiously to further increase the performance of the Macchi M.C. 72 and its engine, but the attempts on the record were foiled by additional technical problems. Finally, on October 23rd, 1934 Agello was ready to try again. The skies that afternoon were grey, almost wintery. A layer of haze made visibility difficult, but the lake was calm as was the air above it. Agello climbed into the M.C.72, its engine already warmed, and set out on the great flight. The four laps proceeded normally and the engine, with its resonating and impressive roar, produced echoes from the mountains around Lake Garda, almost as though they were calling to the ghosts of those heroic high-speed pilots who had fallen in the ultimately victorious desire to bring to the Nation, to Italy, the highest honor and the most admirable prestige.

Agello did it! He completed the four laps over Lake Garda at an average of 709.202 km/h (440mph), despite the annoying layer of haze that partially obscured the course. The FIA team recorded the lap speeds as follows: 1st lap 705.882 km/h (438mph)—2nd lap 710.433 km/h (440mph)—3rd lap 711.426 km/h (441mph) and the 4th lap 709.034 km/h (440mph). The record was subsequently verified by the Federazione Aeronautica Internazionale for the seaplane with the internal combustion engine category (subclass C-2, Group 1). Despite this, both Col. Bernasconi and Agello were not completely satisfied, and they were convinced that with better weather conditions, it would be possible to achieve an even better result. In fact, in the course of an earlier, unofficial flight, the M.C. 72 had recorded speeds greater than 730 km/h (453mph). Unfortunately, with the arrival of winter and the prodigious costs involved with hosting an eleventh record attempt the two men decided to accept their already excellent result with good grace. Later, Colonnello Mario Bernasconi, Comandante of the Reparto Alta Velocità at Desenzano on Lake Garda, would describe the conquest as an unmatchable world record, and so it is to this date for piston-powered seaplanes.

FRANCESCO AGELLO

FRANCESCO AGELLO

Francesco Agello was born at Casalpusterlengo on December 27th, 1902. At 22 years of age, he obtained his pilot’s wings with the Arma Aeronautica. He received his Brevetto di Pilota Militare in 1924, and four years later applied for a posting to the Scuola Alta Velocità of the Regia Aeronautica, which was based at Desenzano del Garda, being admitted on May 15th, 1928, and participating in the first course for high-speed pilots. Initially holding the rank of Sergente Maggiore, and later Maresciallo, he flight-tested nearly all the types of racing seaplanes in use with the Scuola, which was commanded by Colonnello Mario Bernasconi. In 1929 he was a member of the Italian team that participated in the Schneider Cup, and in 1932 won the Coppa Baracca. For the results he achieved, Agello was promoted to Sottotenente and awarded the Medaglia d’Oro al Valore Aeronautico with the following motivation: “High-Speed pilot of exceptional valor and ardor, after engaging in difficult and dangerous test flying for the perfection of the fastest seaplanes in the world. On two occasions he broke the absolute world speed record”. In 1935, promoted to Tenente, he was posted to the Centro Sperimentale at Guidonia. In 1936, now a Capitano, he became a test pilot for the Ufficio di Sorveglianza Tecnica (Technical Surveillance Office) and between 1938 and 1940, he commanded the RAV. Subsequently transferred to Milano-Malpensa airfield as a test pilot, in 1941 he tested the Reggiane Re.2001bis. Sadly, Agello lost his life in a flying accident on November 26th, 1942 when the Macchi M.C.202 he was flying collided with a fighter of the same type flown by Guido Masiero, another celebrated Italian pilot who had participated in the Ferrarin’s Roma-Tokyo expedition.

Thanks to Lugino Caliaro for the article. The author wants to thank Fausto Bortolotti, Alessandro Piccoli, and Francesco Ballista for the pictures and the historical research.

More Photos.

Balbo t’é pasé l’Atlantic,

mo miga la Pérma!

Great article and photos… I loved it!

This has been one of my favorite all time racing planes. Awesome airplane and Pilot Angello. Performance that even to this day is unmatched for piston powered seaplanes. Those pilots have my respect and awe for what they achieved and there bravery.

Any idea why seaplanes during that era were so much faster than land planes?

In 1934 this plane clocked 440, setting the seaplane speed record. A year later Howard Hughes’ H-1 set the landplane record with a speed of 352.

Did something prevent engineers from being able to fit engines like the Macchi’s V24 into a land plane?

Horsepower and aerodynamic floats

Without variable pitch propellers there were no runways long enough for a top speed plane takeoff.

One of my favorite aircraft. It was an amazing feat, that to this day is unmatched. What a beauty and beast the MC72.