Since WarbirdsNews received so much positive feedback on last week’s story featuring L. Doug Keeney’s book Lost in the Pacific, we asked Doug if it would be possible to share one of the book’s adventures with our readers. Doug has graciously allowed us to re-print an excerpt, and it makes for a riveting read. Although most of the hair-raising air/sea rescue tales covered in Keeney’s book take place in the Pacific Theatre, this particular story occurs over Europe. It’s the word-for-word story taken from the logs of 1st Lt. Jack Terzian, a 353rd Fighter Group Thunderbolt pilot who describes an escort mission from April 9th, 1944 where he went down in the English Channel after tangling with a German Fw-190.

Note from the author, L. Douglas Keeney:

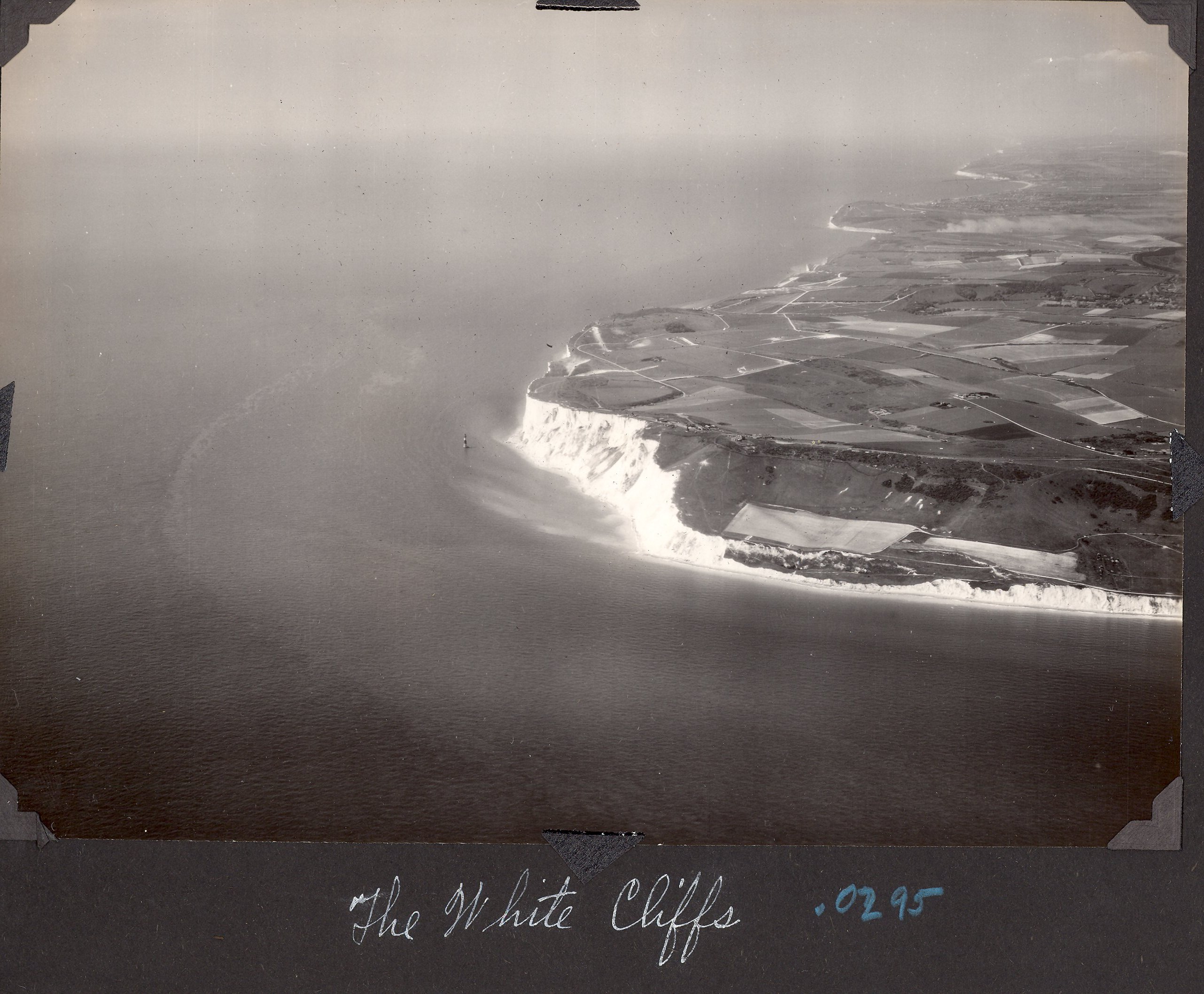

Air/sea search and rescue operations started in the English Channel so Lost in the Pacific includes some of the most interesting ditchings I could find from the ETO. Like most of the stories in the book, its not just the ditching or the survival story that interested me. Rather, it was the sum total of the mission. Here’s a story from a fighter pilot who goes down after escorting the bombers on a raid against German just after Big Week. He knows he has a problem but even after the mission he goes after a German FW-190 which costs him his gas and ultimately forces him to ditch in the North Sea. This is the Greatest Generation at its best.

Roughman Red:

On the 9th of April, 1944, I was flying in Roughman Red Flight #2 position. When we made landfall (L/F) in, my wing tanks ran dry, so I dropped them. I noticed a smell of gas in the oxygen system, but gave it no thought. Soon afterwards, Skybird called to withdraw from the bombers. I removed my oxygen mask and smelled the cockpit. It smelled of gas, and I realized the possibility of a fuel leak. I still had plenty of gas, so I was not worried. I switched my oxygen to the “Off” position which eliminated the smell of gas.

Captain Byers, my flight leader, and I spotted an a/f, and I hoped we would attack it, which we did. No. 3 and No. 4 of the flight gave us top cover while we went down. I was slightly higher and about ½ miles line abreast of Capt. Byers when a FW 190 went between us in the opposite direction. Capt. Byers told me that it was a FW and I turned upon it as it made a 180 degree turn to go after Capt. Byers. When the e/a saw me he turned into me and we exchanged fire head on, no hits. I pushed everything forward and went into a sharp climbing turn to make another pass at the e/a. I out-turned him but could not get enough deflection on him. We exchanged fire again, and I observed no hits. The e/a broke off the attack and headed West. I decided to chase him and was gaining on him until I hit detonation. I was running an automatic lean. Before I broke off my pursuit, I was about one mile behind him so I gave him about two rings vertical deflection and fired a burst. I noticed him turning to the left and flying closer to the ground. I turned around and took a heading of 240 degrees and flew on the deck until I made L/F out and climbed up to 8,000 ft. Capt. Byers tried to locate me during the engagement but I had gone inland too far for him to do so. I ran out of oxygen at that time and the odor of gas fumes was terrific. I had about 140 gallons of gas left and figured that I might make it. I throttled back to 30″ of mercury and 1500 RPM. As my gas was going down fast, I took a heading of 248 degrees and flew along the Frisian Islands as was planned. It was hazy and I could not tell exactly where I was and how much further I had to fly before leaving the Islands. As I noticed my gas going down further, I pulled back to 1400 RPM and knew then that I would not be able to make it home. I do not remember what time that was. I thought of expending all my ammunition and did so. Some 10 or 15 minutes later, I was indicating 40 gallons of gas and called anyone in Roughman Squadron if they could find me so that I could have an escort until I bailed out. Lt. Maguire’s flight turned back and found me. I called for Mayday but could not be heard. While Lt. Stanley, Lt. Crampton and Lt. Furness flew alongside of me, Lt. Maguire gained altitude and tried to call for Mayday. They received him and told us to fly a course of 260 degrees. I tried again to call Tackline control. They would receive me but could not get a fix on me at the time. Lt. Maguire called again a few seconds later and they did get a fix and told me to fly a course of 255 degrees.

My gas was down to 30 gallons. I tried to remain calm while Lt. Maguire continued to call a Mayday for me. We had left the islands about five minutes before this. My gas gauge remained at 30 gallons for about 10 minutes when the engine quit. I switched to my auxiliary tank to see if I could get any gas out of it, but it was dry. I got a surge of power and the engine quit again. I switched to main again, got another surge of power and the engine quit again. I switched back to auxiliary – no gas. Switched back to main – no gas. I gave Tackline a last call and told them I was bailing out. I also said so long to the fellows who were escorting me. I was at 5,000 ft. and had plenty of time, so I unloosened all connections to my body and tried to roll the ship over on its back which I think I should not have done. The ship went into a split “S”, shuttered and started to spin. At that time, I let everything go and climbed out the right side. As I was getting out, I saw myself sliding along the fuselage towards the tail assembly. I grabbed the right side of the canopy with my right hand, pressed myself against the fuselage with my left hand and as I climbed out, my feet were slammed against the fuselage. I pressed my feet against the fuselage and pushed away from the a/c going down backwards. I believe my left little finger hit the horizontal stabilizer. I received no jolt when I pulled my rip cord. I seated myself well in the chute and undid the leg harness. As I got near the water, I undid my chest strap. I was descending slowly and I entered the water in a sitting position, releasing myself from the chute and inflating my Mae West at the same time.

I did not go under water at all. I had no trouble getting into my dinghy, that’s to my dinghy drill some several months ago. The water was rather cold and even after I got into my dinghy and baled all the water out, I shivered all the while. Lt’s Maguire, Crampton, Stanley and Furness must have stayed with me for about 2 hours. Their buzzing and circling around me was a great morale factor. They were like God watching over head. Before they had to leave, another ship arrived over me and took over. The weather was closing in faster and I could see this plane going in and out of the fog. It led me to believe he lost sight of me. I tried using my flares. As the roar of the engine got louder, I pulled the pin in the first flare, it did not work. I tried that 3 times, all three flares failed to work. I did not know whether he lost sight of me, but things began to look black. The weather was getting bad and I was preparing myself for an all night stand. I emptied my escape kit and put the different things in different pockets so that I would know where to find what I wanted at night. I chewed a piece of gum which helped. I tried a Malted Milk tablet but it seemed to make me more thirsty. However, food and water did not concern me much as the time. About 4 hours after I was in the dinghy, 2 bombers passed overhead. I waved the flag I had but they did not see me. At each sound of a plane, I would look around to see where it was, but could not find it. This discouraged me to no end. It got so that I was too afraid to look for any more planes for fear they would be going in another direction and discourage me some more. All this while I was trying to make myself comfortable but could not do so. The water began to get choppy and the weather worse. 3 more P-47’s came out of the West, did a 180 degree turn around me and headed back West again. Whether or not they saw me I do not know. They gave me no indication of it. Things began to look blacker yet. Sometime later, I heard another a/c approaching, so I turned around to see if I could see it. He was circling nearby and as I looked West, I saw the silhouette of a gray launch approaching me head on from out of the mist. It was the prettiest sight any one could see. From there on it was smooth sailing, although it took me about 2 hours to thaw out and the injury to my left ankle became prominent.

My most profound appreciation and gratefulness to Lt. Maguire for his smart head work and determination, and also to Lt’s Stanley, Crampton and Furness and Lorance, and also to Lt. C.W.S. Sheppard and his crew of HMS Midge and all concerned in bringing about my rescue.

“Roughman Red”

Excerpt from Lost in the Pacific, L. Douglas Keeney

Excerpt from Lost in the Pacific, L. Douglas Keeney

Copyright 2014 L. Douglas Keeney

Photo Credits: Authors Collection/National Archives

To buy LOST IN THE PACIFIC: Epic Firsthand Accounts of WWII Survival Against Impossible Odds click HERE.

Be the first to comment

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art